Comisiones

a destiempo

Provenance.

Carla Rippey’s Eleven Engravings

in the ESPAC Collection.

Daniel

Garza Usabiaga

Carla Rippey’s Eleven Engravings

in the ESPAC Collection.

Daniel Garza Usabiaga

Art historian and independent curator.

I am grateful to Carla Rippey for her generosity and time for this publication.

I am grateful to Carla Rippey for her generosity and time for this publication.

ESPAC’s collection holds eleven engravings by Carla Rippey produced between 1975 and 2009. The first group of works—made between 1975 and 1986—was acquired via an intermediary, while the second—created between 2004 and 2009—directly with the artist.

Evident changes in Rippey’s production can be observed in these eleven engravings. However, they also serve to apprehend her sustained and constant interest in the image, its analysis and its subversive resignification. Rippey’s investigation of printed or photographic sources and her employment of conceptual strategies—such as framing, juxtaposition and the articulation of narratives through fragments—can be appreciated in the pieces. These matters are present in the totality of her production, which in addition to engraving, also includes drawing, photography, painting, ceramics and objects.

For this exercise regarding the study of a set of works in ESPAC’s archive, I asked Carla if it was possible to see the inventory of the pieces under her authorship. She responded with a series of comments (annotated in this color). I interviewed her based on that information. Some of these questions and answers are written in italics and alternate (next to original comments on the engravings) with fragments that I extracted from some of Rippey’s past lectures (which appear here in bold, accompanied by their respective references). The idea is to give continuity to the play of fragments and narrative articulations that are employed in her production.

Carla Rippey.

Sol, 1975.

Copper engraving (soft varnish and aquatint),

28 x 30 cm.

ESPAC Collection.

I studied in Old Westbury, SUNY’s experimental school. My only art teacher was Luis Camnitzer, but he only taught me about attitude, which was perhaps the most important thing I could learn! He was my thesis advisor. My thesis was about the intersection of art and politics.

CR: In 1972 I went to Chile and married Ricardo Pascoe. I made silkscreen posters for the Movimiento de Izquierda Revolucionaria (MIR) [Leftist Revolutionary Movement] and learned to engrave. We arrived in Mexico after the military coup and I started working in a collective workshop called Molino de Santo Domingo (my brother in law from the Martín Pescador workshop took me there). At the beginning, my iconography was limited to plants and other organic matter because I felt like I hadn’t developed a language of my own to address the human figure (I had tried it in Chile, but I wasn’t satisfied with the result). This engraving and another one titled Luna (in blue tones), were my first attempts at drawing people, so it has some historic relevance!

I worked in this style and its variations until around 1980 when I started using frames or photomontages as references, despite de general prejudice against working from photographs.

Carla Rippey.

Sin título, 1976.

Zinc etching (Soft varnish and aquatint),

33 x 28 cm.

ESPAC Collection.

This engraving is from the same stylistic period as the previous. As I typically did, I made a series of color tests (this is one of them), signed them all as A/P (Artist’s Proof) and never made a uniform edition.

DGU: What were the engraving cliques like when you first got to Mexico? How did you perceive that specific context?

CR: Everything was changing. Associations like the Taller de Gráfica Popular (TGP) [Popular Printmaking Workshop] were considered obsolete. I think these changes were caused first by La Ruptura [The Rupture] (Neoliberalism!) and then by the events of 1968. Felipe Ehrenberg for example, left Mexico around that year and with Martha Hellion created Beau Geste Press. They connected with Ulises Carrión and Jan Hendrix and everything started to move in another direction. Martha and Jan took a more aesthetic road and Ehrenberg (not aesthetic at all) opted for Los Grupos [The Groups]. I am not really sure how, but I met Ehrenberg, who in 1976 got me in The Culture Workers Group even though I still wasn’t part of any group! I then met Adolfo Patiño. Camnitzer introduced me to the gallery of Esperanza Bolland, sister of his sister-in-law Isabel, who was married to Luis Porter. There I met Adolfo, who arrived with Esperanza because of Gurrola. Adolfo met Gurrola in Churubusco Studios—where he would hangout taking pictures of, for example, the Fando y Lis shooting—and decided to pay Gurrola a tribute in the gallery. At that time, Patiño was 22 years old. I met him a year later when I was 27 and had two children.

We were interested in what Francisco Toledo and José Luis Cuevas were doing in printmaking, both were very proactive. I remember taking a special notice in the series Toledo made using a rubber stamp with Benito Juárez’s face and also in his monumental sculpture La Giganta (The Giant Woman). The DF-Oaxaca-Paris fusion. With López Quiroga, I also saw the Toledo series in which he uses a “progresive plate” (I bet he has another term for the process), which begins with rabbits jumping on boxes and then changes and changes, as if erasing and then adding with a drypoint and a burnisher. The rabbits disappear, a blind man enters, a cage with a lion inside it appears. It’s hallucinating! There are about fourteen images. I have never seen this series reproduced, but I would love to see it again. This is where I got the inspiration for the Viajes a las piramides [Voyages to the Pyramids] series from.

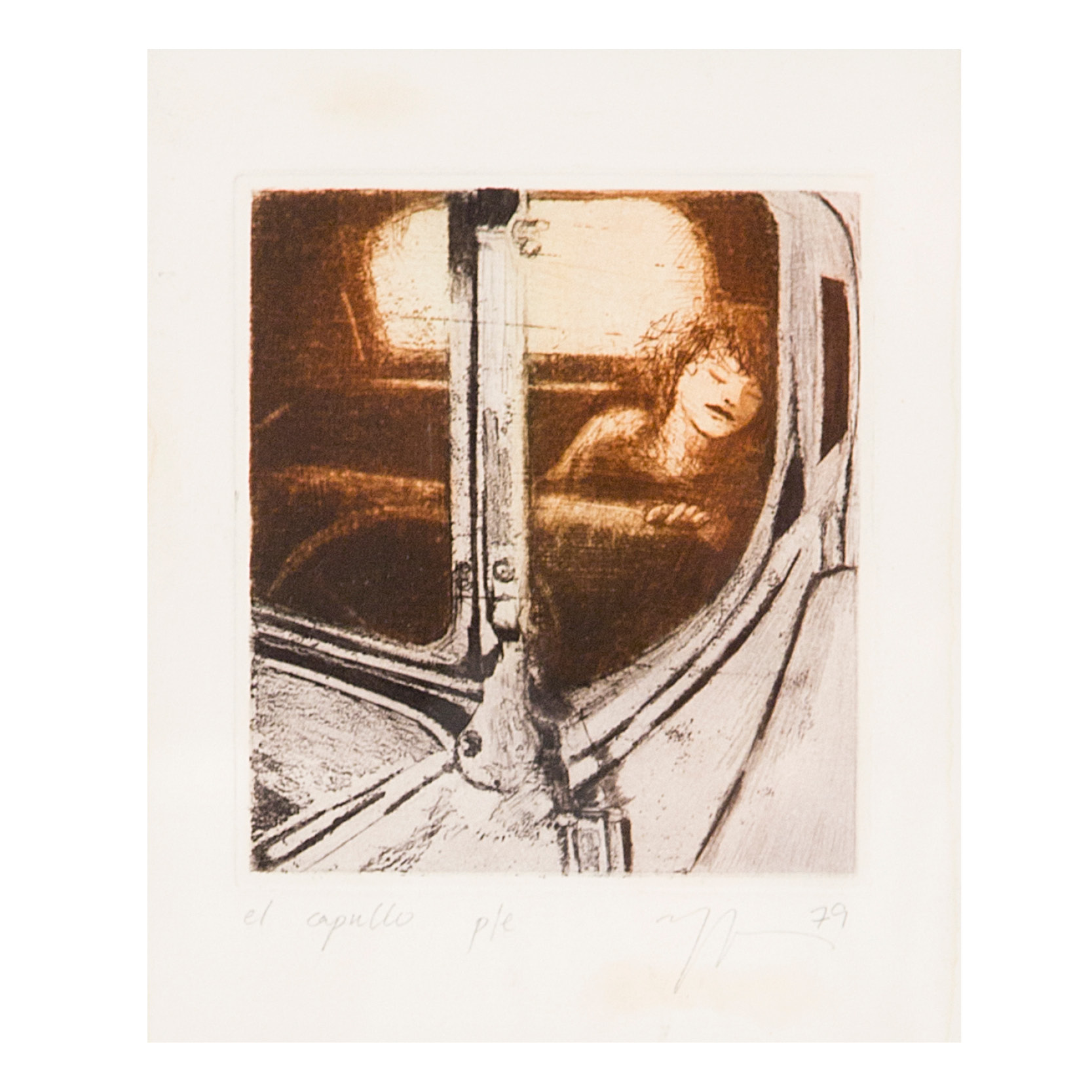

Carla Rippey.

El capullo, 1979.

Copper engraving (Soft varnish and drypoint),

21 x 18 cm.

ESPAC Collection.

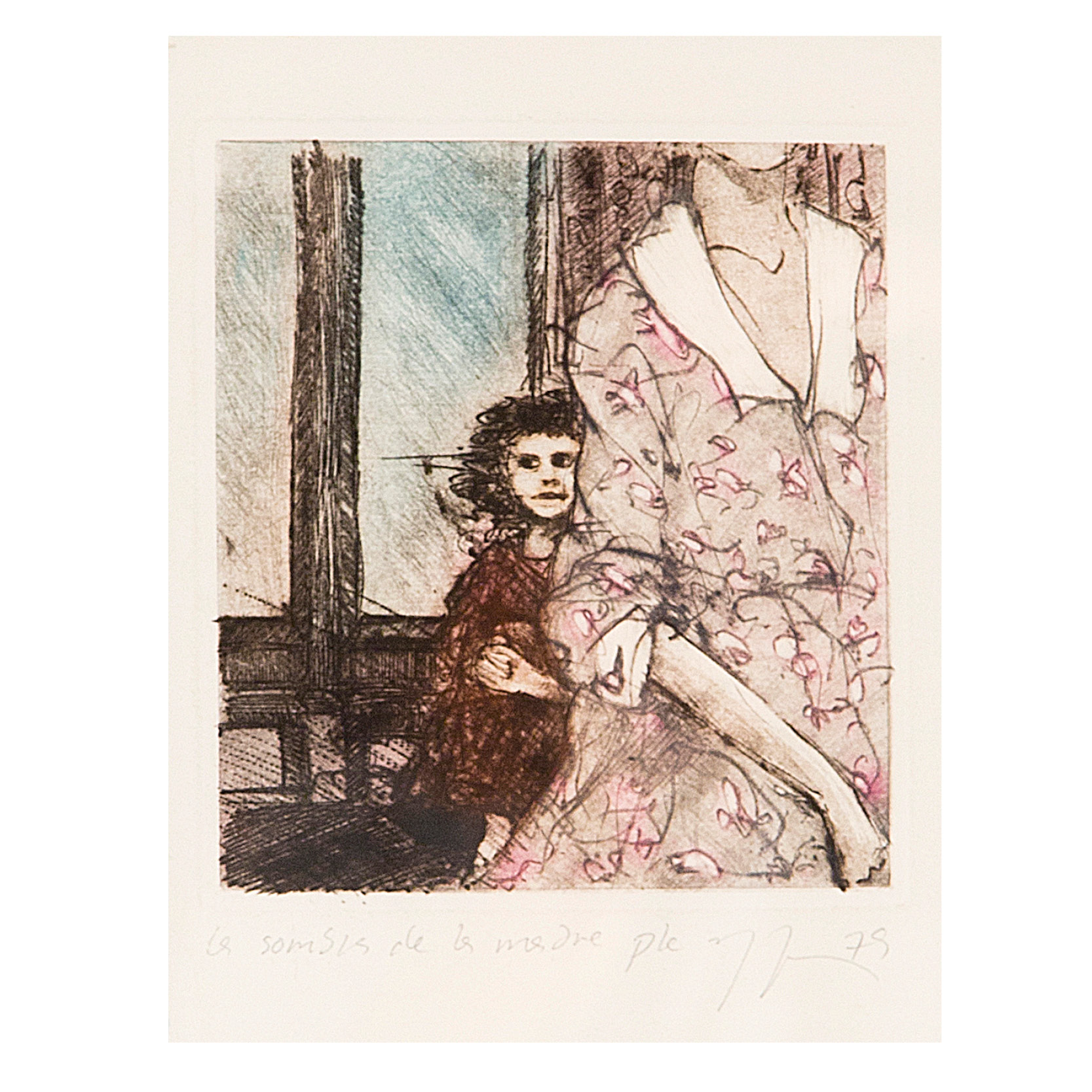

Carla Rippey.

La sombra de la madre, 1979.

Copper engraving (Soft varnish),

15 x 13 cm.

ESPAC Collection.

El capullo [The Cocoon] and La sombra de la madre [The Shadow of the Mother] are part of my first thematic series (composed of twelve engravings called Pequeñas revelaciones [Small Revelations]. The mother piece is from the same stylistic period as the two previous engravings, but in El capullo you can see I am working from a photo to a certain degree. During this period I would always do the printing myself and in general I would only print a few copies at a time. If I sold them, I would print more.

My husband and I were already separated and I would sustain myself and my children through the sales of my work (except for five years, between 1980 and 1985, when I was a printmaking professor in The University of Veracruz, and thus I was accustomed to making small engravings because they were easier to move in the market. Well, at least in the one that I had!

DGU: Your use of photographs speaks of a constant interest in the image, matter you were investigating since then through multiple media, printmaking was only one of them. An example is the experimental work that you produced with the art group Peyote y la compañía [Peyote and the Company] at the same time that you made these late seventies engravings. You previously mentioned that there was a prejudice among the printmakers’ guild towards the use of photography.

CR: Those were very neo-figurative times. The attention was on Cuevas, Aceves Navarro and Toledo. It is interesting that Toledo’s recognition increased, Aceves Navarro’s persisted and Cuevas’s was overshadowed...

Still, if I worked from a photographic montage in El Molino they would say, “Rippey rips-off photographs!” Nevertheless, I was so attracted to this process that I insisted on it and soon after the word got out of the kind of work David Salle and Eric Fischl were making and the term “appropriation” was invented and all of a sudden it turned out that I was “postmodern.” It was very common for Patiño and me to be doing experimental things and then seeing something similar in US art magazines. And yes, that always “perverted,” as Olivier Debroise used to say, the original intent of the photo; it subverted it.

Versiones del Paraíso, 1979 y La huida del burócrata, 1979. Courtesy of the artist.

CR: Without a doubt, printmaking was only one of the media I investigated. I was trained in photography. I would read Life and Look magazines and Edward Steichen’s book The Family of Man (1955). It was long after I realized that Steichen’s texts, his juxtaposition of images and his structures of narrative were a big influence in my way of working. My mom was dedicated to literature (she was a Doctor in English Literature) and my dad was (for a long time) a photojournalist. He was a great photographer and a skilled writer. They were some of my other influences.

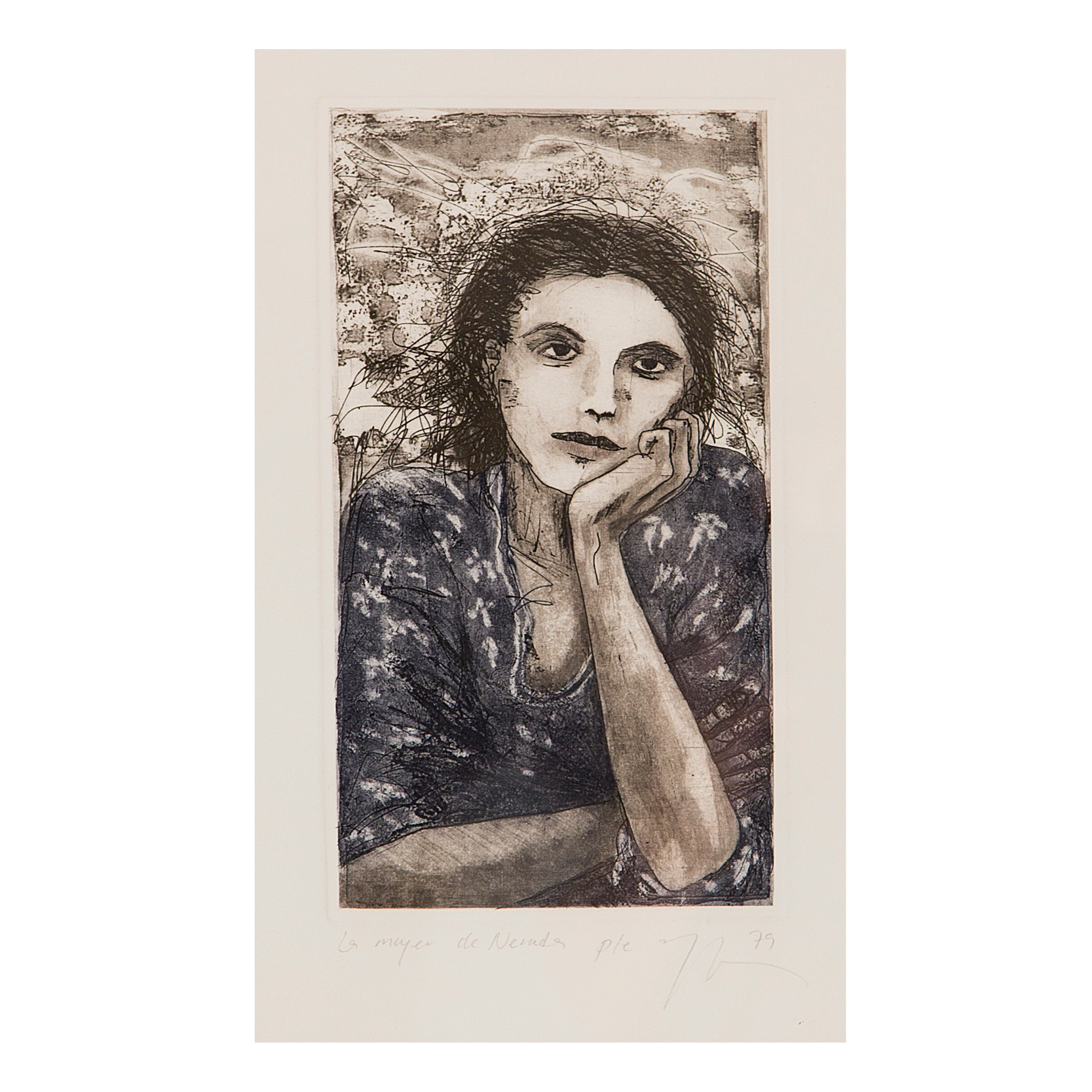

Carla Rippey.

La mujer de Neruda, 1979.

Engraving,

27 x 14 cm.

ESPAC Collection.

This engraving was part of an edition I made for a politician. I believe I convinced Juan Pascoe to print a poem by Pablo Neruda to go with it. The poem was printed in the same sheet of paper so this piece is a proof.

Carla Rippey.

Sin título, 1983.

Drypoint and watercolour,

19 x 16 cm.

ESPAC Collection.

This engraving belonged to a tryptic I finally resolved with a chine collé made with starry wrapping paper.

CR: Esteban Azamar, a friend of Patiño and mine from Xalapa, started to draw from photos at the same time I was working with old photographs and with Eadweard Muybridge’s work. In terms of conceptual strategies, I was more exposed to Adolfo’s, who even though he didn’t finish highschool, was very curious and always kept an eye on the international scene. Just for fun, I used to help him costruct and resolve his pieces. Though he did assemblages, we were both working with the concept of collage. In 1988 I put on a show of object pieces in el Chopo named Todas las cosas de la nada [All the Things from Nowhere]. I always thought it was more fun to make object-art than to draw. My assistants were Patiño and Gustavo Prado. Brilliant combination. If you observe the pieces you can see that almost all of them have a graphic element.

Carla Rippey.

Viaje a las pirámides, 1983.

Copper engraving (Drypoint with chine collé),

25 x 25 cm.

ESPAC Collection.

CR: Viaje a las pirámides was part of an extensive series of processed engravings. This means that I would make the image, print whatever number of copies and then I would change the plate, erasing and redrawing. Olivier Debroise used this and another image of the series for the cover of his book En todas partes, ninguna [In Other Parts, None] (1986).

Adolfo and I would gather a lot of material from the books and stationary shops in Xalapa. In the back area they stored all the material they hadn’t sold since the twenties and it could be bought cheaply. That is where Adolfo got the Italian diagrams for his piece Autorretrato como Xipetotec [Selfportrait as Xipetotec] (1985-1986). I started printing on different antique books, corny postcards and calligraphy manuals. This was in my pyramids and volcanoes periods. This is the complete series, only three plates were used.

Viaje a las pirámides, 1983. Courtesy of the artist.

Viaje a las pirámides, 1983. Courtesy of the artist.DGU: Thinking about your interest in the image, in Viaje a las pirámides one can appreciate your predilection for fragmentary structures that could be understood almost like cinematographic sequences or that, as a whole, pose different associations that can be made by the spectator.

CR: I am very interested in creating narratives. Along with juxtaposition and framing, it’s a fundamental part of my work, particularly in the artist books. Appropriation and fragmentation are also traits of the collage. I have always felt that the twentieth century was the century of the collage and the twenty-first is of the virtual.

Framing is one of the resources I must employ to articulate my intention; I use it to direct the eye to what most interests me. Many times the intention or perception of the image can be changed by using a different frame. Then comes juxtaposition. When two images are placed together a forced relationship capable of changing the perception of the matter addressed is created.

My idea of narrative is one in which the story I want to tell or the situation I want to create is what enables the reading of the work or the appreciation of its meaning. The term applies particularly to the works that are presented as a sequence. 1

Carla Rippey.

La chispa, 1986.

Etched on zinc (soft varnish),

30 x 36 cm.

ESPAC Collection.

La chispa, 1986.

Etched on zinc (soft varnish),

30 x 36 cm.

ESPAC Collection.

This engraving is done in a looser style characteristic of the seventies, but is based on a photo.

DGU: In 1985 you were the only woman that participated in the show De su álbum… inciertas confesiones [Of Her Album… Uncertain Confessions] curated by Olivier Debroise in MAM (Mexico City’s Museum of Modern Art). This show brought the aesthetic of postmodernity and the interest in the image to debate among a group of artists of your generation (in the case of this show mostly painters). How familiar do these debates sound?

CR: I don’t really remember what I exhibited on that occasion. It might have been Tres tardes en el jardín [Three Afternoons in the Garden], one of the few paintings that I have done that I actually like.

Tres Tardes en el Jardín, 1986, Oil on canvas,100 x 70 cm c/u, Courtesy of the artist.

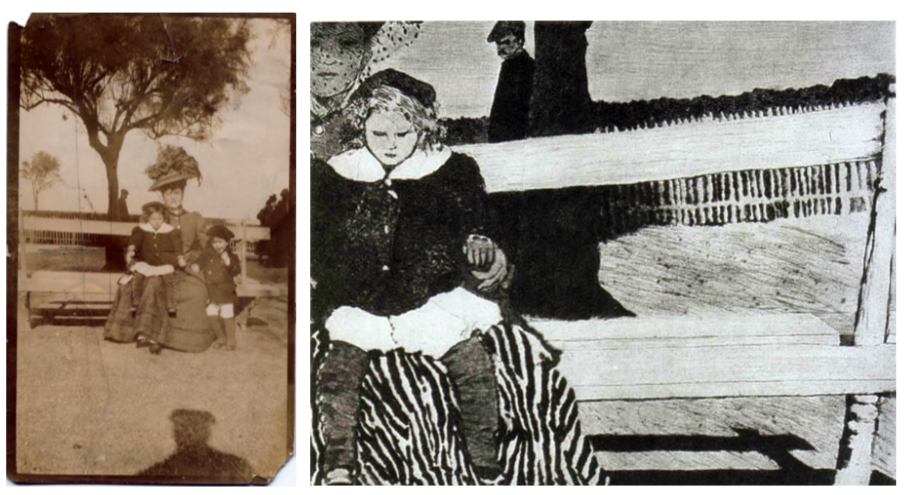

Tres Tardes en el Jardín, 1986, Oil on canvas,100 x 70 cm c/u, Courtesy of the artist.In the catalogue text Olvier mentions El vigilante [The Watchman]. I am placing it next to the photo from where I got the image so the change can be seen:

I sensed a not obvious threat in the original photo.

Though I read a lot, it generally wasn’t theory, but mostly novels and stories. I would rather see images. For his text for my solo show at MAM, El sueño que come al sueño (The Dream that eats the Dream) in 1993, Marnique curiously places me as the forerunner of postmodernity in Mexico. Sometimes I stumble upon theory and that illuminates an aspect of my work. This happened Recently, for example, when Magali Lara shared a text by Griselda Pollock that I used in a talk I gave on photography and gender.

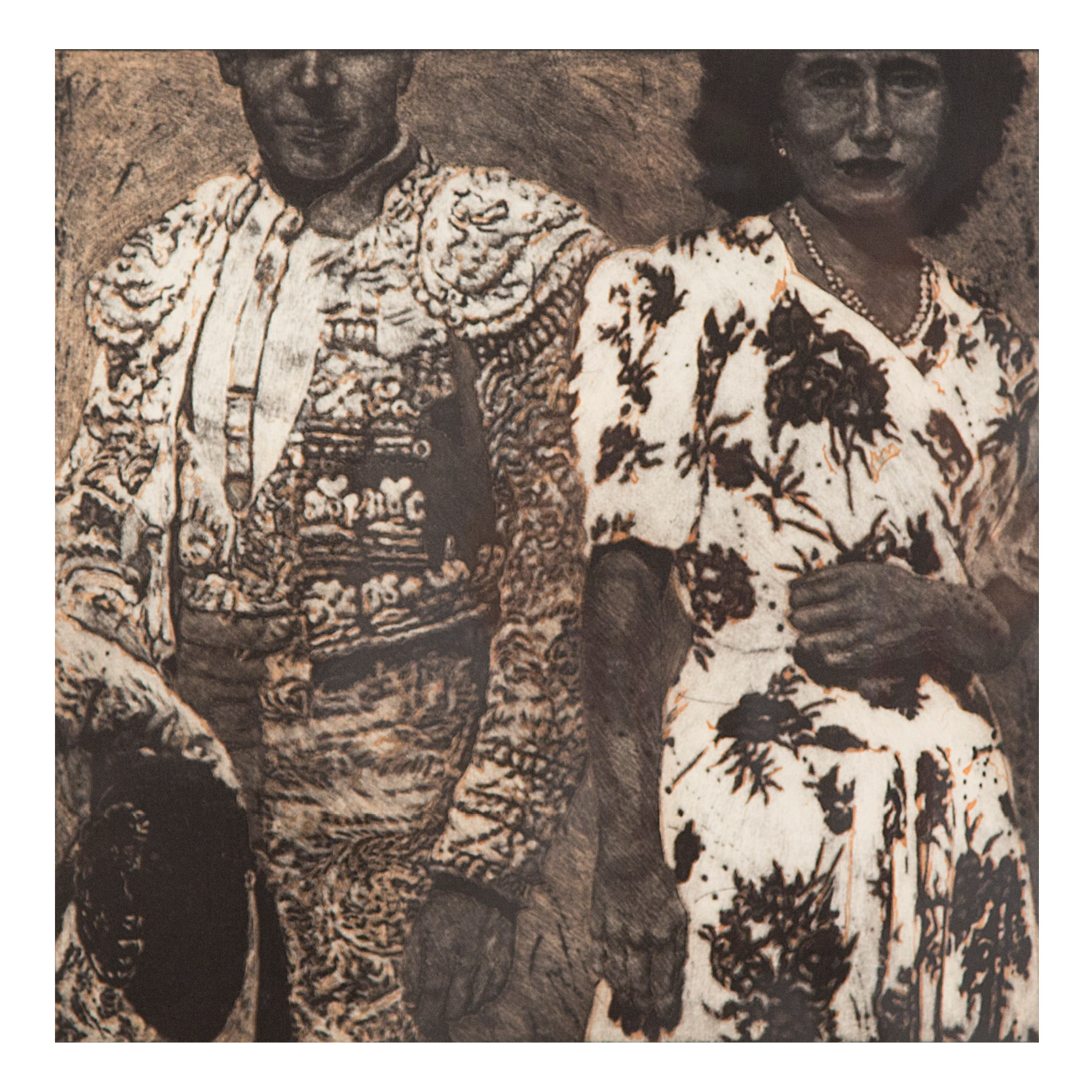

Carla Rippey.

La mujer del torero, 2004.

Copper engraving on two plates (Drypoint and aquatint),

30 x 30 cm.

ESPAC Collection.

Since it depicts a couple, on many occasions I sold La mujer del torero [The Bullfighter’s Wife] for weddings. I recently learned of a woman who a long time ago had presented it as a wedding gift. She told me the situation was a mess because the groom was a bullfighting enthusiast and was deeply offended by the bullfighter’s icomplete head. He thought it was an aggression. Sigh…

I had a few pictures of this woman with bullfighters so I did several works around her. This engraving is based on the following photograph:

CR: Wallpaper and floral dress motifs keep appearing and reappearing in my work. That, along with the bullfighters costume, is what drew me to this photograph. I grew up surrounded by these types of images and by an English aesthetic that came from the illustrations of the books I was looking at. Years later, I think I became obsessed with Asian aesthetics because it’s latent in the Victorian, which has a strong indian influence, for example. Similarly, for a long time it was very common to see female subjects in my work. I used to make women the focal point of the composition. On the one hand, through the work I was resolving my own relationship with the world, but on the other hand, a piece with a female subject is very appealing, and I lived off the sales of my work.

Before going to Chile to participate in the Revolution and get married, I lived in a feminist commune in Boston. There, I learned rudimentary screen printing processes because of women protests and other activities of the sort I was engaged in. In Mexico I never joined a feminist group (I never found any). As a matter of fact, Los Grupos were mostly composed of men and if there was a woman present it would typically be the girlfriend of one of the leaders (Take a look at Peyote and Proceso Pentágono). Moreover, the pieces with erotic themes that I developed over the course of many years, were often perceived as antifeminist for showing nude women.

Because of my inclusion in the exhibition Radical Women. Latin American Art. 1960-1985 I realized the way I addressed the notion of the body was different from my contemporaries. In them, I saw a tendency to work with their own bodies or to register other women’s bodies, and in the process register images that were distinct from the socially constructed image or from male appreciation. Meanwhile, I would set out from these stereotyped images to try to shed a new light on the way we read photographs that were created to satisfy male fantasies.

I started working from photographs in the early ’80s. It was then that I began exploring the representation of women as objects of desire and began to look for possible ways of reinventing these images. In this process I observed that I have an inclination towards disturbing the expectation that sustains the original erotic image.2

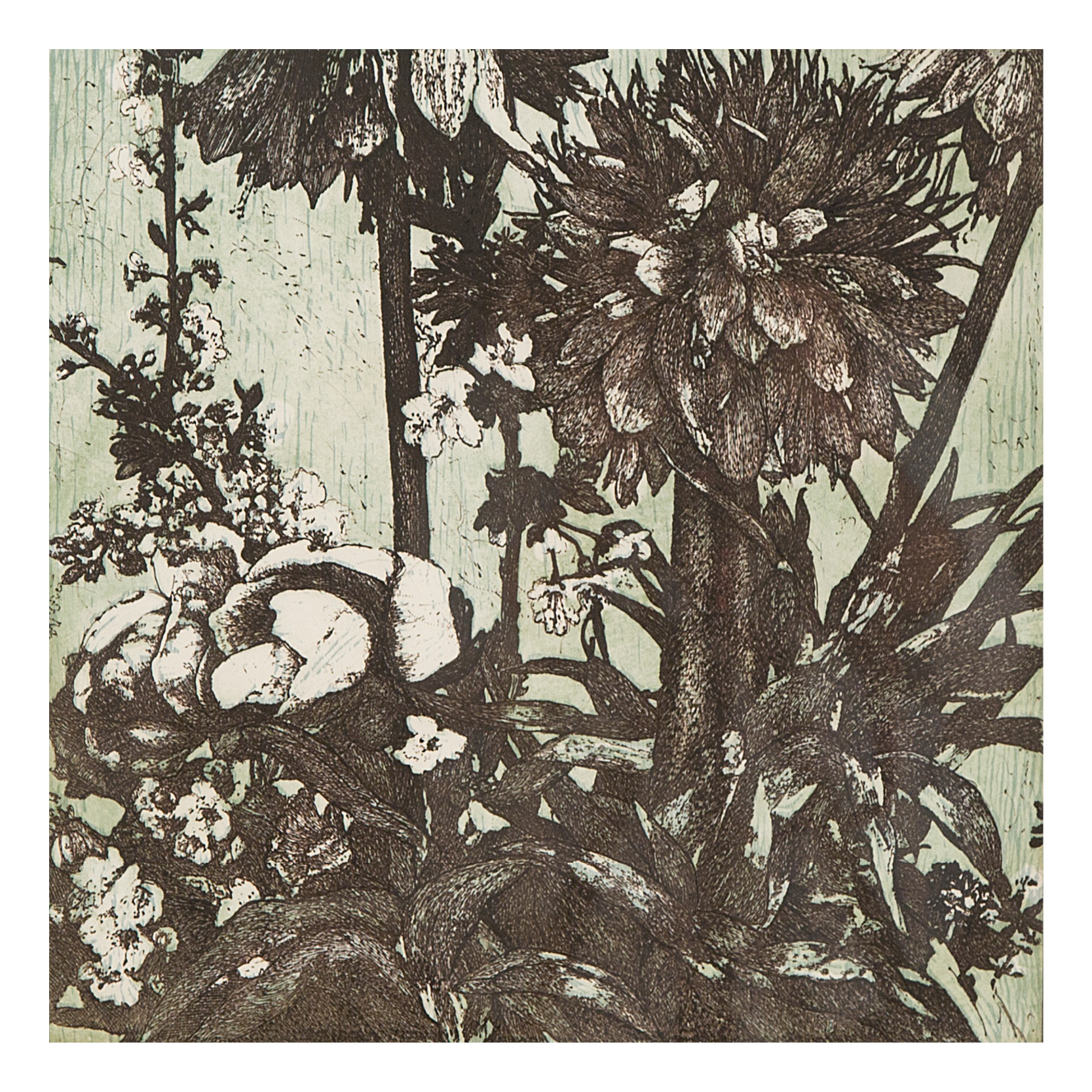

Carla Rippey.

Selva doméstica, 2005.

Wood, metal and acrylic engraving. 3 plates.

40 x 40 cm.

ESPAC Collection.

Even though this engraving had three plates it never excited me much. I could have probably resolved the color better.

Another type of printed material that had an overwhelming presence during the nineteenth century and great part of the twentieth, at least in Europe and The United States, was wallpaper. Though I haven’t seen much evidence of its use in Mexico. However, its use was not always a success. There were many cases of poisoning in England due to the use of arsenic dyes in the fabrication of certain kinds of wallpaper. All of my family’s homes were covered in wallpaper, a circumstance which was later reflected in the iconography of my work…

For some time now, in less privileged social strata, like in the Appalachian region in the United States, magazines and newspapers have been recycled to serve as improvised wallpaper.

Besides this one, there are many other examples of the omnipresence of the printed form and the ways in which we have incorporated it into our lives could be added. What I’m interested in highlighting is that the printed image permeates our lives not only through its original intention of use, but also in all of the other secondary uses we invent for it.

Long before it was possible with the moving image, printed forms gave us a bank of malleable images subjected to be collected and intervened. Although film/cinema was greatly commercialized throughout the entire twentieth century and television throughout the second half, it was until the beginning of the twenty-first century when the virtual era allowed a general access to the capture and manipulation of moving images.3

Carla Rippey. Culture Shock, 2009.

Engraving on Japanese kozo paper. 8 parts, 80 x 80 cm each. ESPAC Collection.

Engraving on Japanese kozo paper. 8 parts, 80 x 80 cm each. ESPAC Collection.

Culture Shock interested me greatly and I worked with these images significantly.

What I like is that every part is connected and extensions or variations can be made. I also like the idea of the hybridization of cultures.

I worked with big linoleum plates and with these original images:

Una proviene de un libro sobre telas que los rusos vendían a los nómadas de Asía Central y la otra de manga. Then I would invent combinations like this one (it’s the sixth from left to right)

I did a lot of combinations with plates like this (Sushi heroico) [Heroic Sushi]:

In the mid 2000s, my work in printmaking changed a lot. I began teaching in La Esmerlada (a visual arts university in Mexico City) and my students inspired me to become more inventive. I started to use transfers in my printmaking pieces, technique I had only previously used for my artist books.

The fact is that La Esmeralda helped consolidate changes that were already in process. This happened, because just like with Patiño, I like to work in a team, it is very stimulating. In fact, I got the job in the university because I was longing for more fluid work connections. I later started working in the administration for similar reasons.

Aside from the stimuli of working in a team, I believe that two things that positively influenced my work were: the commercialization of the laser photocopier around 1990 (which I use in all of my artist books and most of my printmaking work) and later Photoshop, which I started to use around 2000 (everything I do goes through Photoshop, it helps a lot with conceptualizing and editing).

Carla Rippey, Bondage, 1998.

Transgraph and drypoint on pianola paper 8 parts, 28.5 x 1000 cm, Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporáneo Collection. Courtesy of the artist.

CR: The works I made using transfer processes did not only encompass engravings, but an array of techniques: In Bondage (1998), for example, I printed photocopies of drypoint works which were enlarged to letter size in a pianola roll (this piece is part of MUAC’s collection and was in the show Reverberaciones [Reverberations], 2017); I also used transfers to make artist books, as backgrounds for pieces and to make other printmaking works based on transfers. Another example of a work done using transfers, realized prior to me entering La Esmeralda, is the installation America en extremo (America in Extreme), created for a symposium in 2001 of Mexican and chicana women artists.

Carla Rippey.

Choose your weapon: Catálogo de objetos peligrosos, 2009.

Photo transfer and silver thread on Japanese paper. Courtesy of the artist.

Photo transfer and silver thread on Japanese paper. Courtesy of the artist.

Another work based on photocopies is Choose your Weapon: Catalogue of Dangerous Objects (2009). It was done using silver thread on Japanese paper and is composed of eight pieces arranged in four frames. If you pay attention, it follows a sequence that begins by hooking you and ends up crucifying you! I took notice of this once the work was finished…Looking for a way to renew my iconography, in the early 2000s, I started to search for images online, which I would capture and incorporate to works and to artist books via transfers. Choose your Weapon, was the result of a Google search of the phrase “dangerous objects.” It is part of the series Mujeres, fuego y objetos peligrosos [Women, Fire and Dangerous Objects], which I began around 2010.4

1. Carla Rippey, “Historias hechas de otras historias – narrativa y apropiación en obra gráfica” [Stories made out of other stories – narrative and appropriation in printmaking works].

2. Carla Rippey, “Fotografía y género – un asunto demasiado personal” [Photography and gender – a very personal matter].

3. Carla Rippey, “Historias hechas de otras historias – narrativa y apropiación en obra gráfica” [Stories made out of other stories – narrative and appropriation in printmaking works].

4. Carla Rippey, “Historias hechas de otras historias – narrativa y apropiación en obra gráfica” [Stories made out of other stories – narrative and appropriation in printmaking works].